How My Chicago Childhood Lead Exposure Connects Me with One in Three Kids Today

I was one of hundreds of millions of children exposed to lead as a child, policymakers and philanthropists are taking bigger steps to combat this today

I still remember getting lined up and taken to the school library. My entire class, like many schools in Chicago, had to have blood drawn to test for the level of lead.

Lead is a heavy metal that, when it enters the body, displaces other chemically similar ions and disrupts the body’s ability to produce necessary proteins. For children, whose brains and bodies are still developing, the resulting consequences are severe: lead reduces IQ, causes anemia and kidney damage, impulse control problems, and at high exposure levels can cause severe physical problems or even death. What makes lead especially insidious is that these effects are often invisible and permanent.

I recall falling just short of the threshold they were using to determine if additional intervention would be required—10 micrograms per deciliter (mcg/dL) of blood. I was lucky. Some other children in my class were not so fortunate.

Little did I know that decades later, I would lead a think tank whose research would contribute to a growing movement to eliminate lead exposure for children worldwide.

The US lead problem and progress from the 70s to today

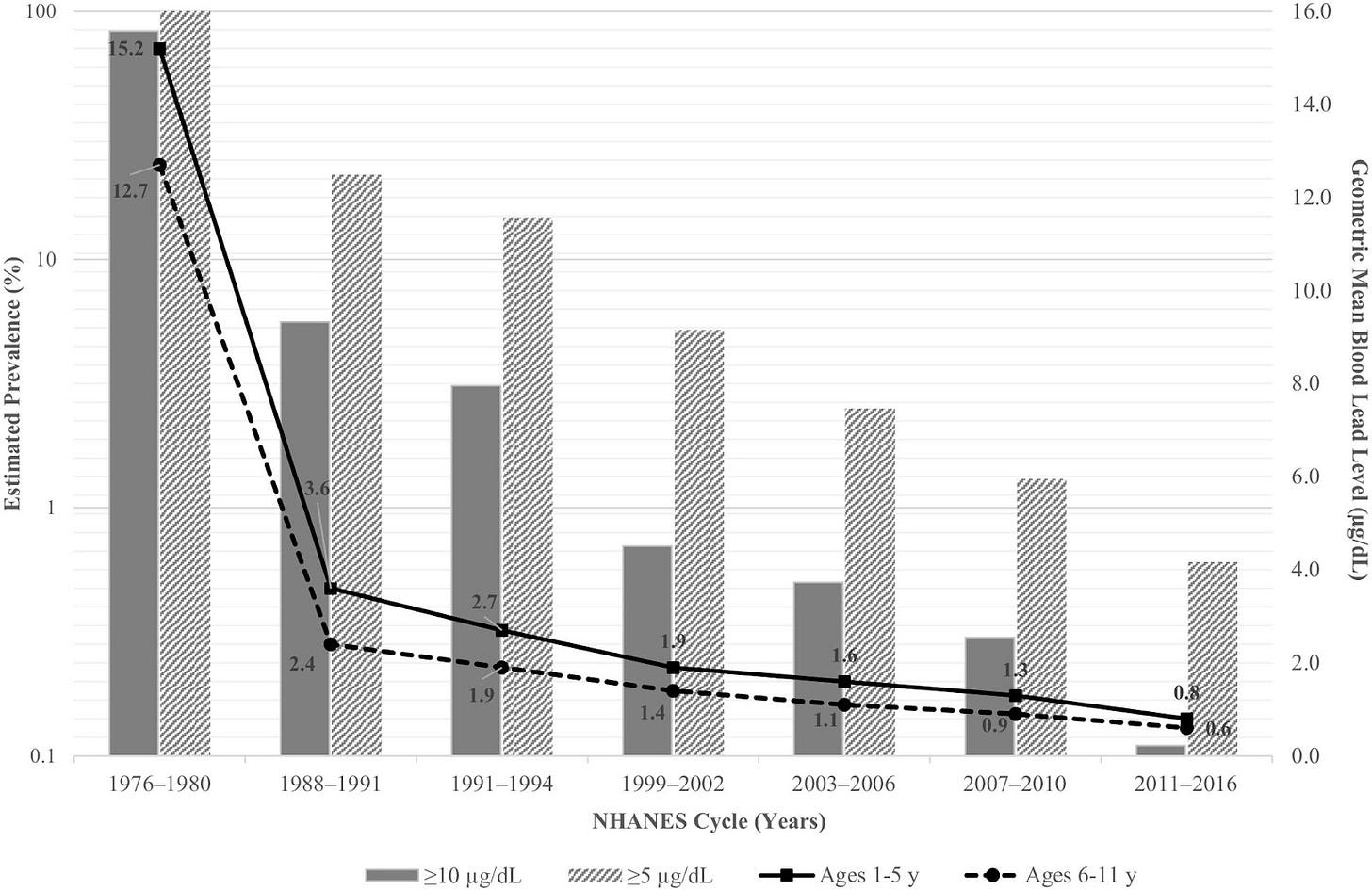

To understand just how dire things once were, consider this: in the 1970s, about 88% of American children had blood lead levels over that same 10 micrograms per deciliter threshold I barely escaped. By the time I was getting tested in the 90s, this had dropped dramatically to around 9% of children—still alarming, but a massive improvement. The discontinuation of leaded gasoline likely contributed heavily to this decline, but continued exposure from other sources in the environment, including lead pipes and paint on older housing stock, meant that millions of children faced significant lead exposure in key developmental years. The burden wasn't shared equally: children who were poor, lived in cities, and were black faced disproportionately higher risks.

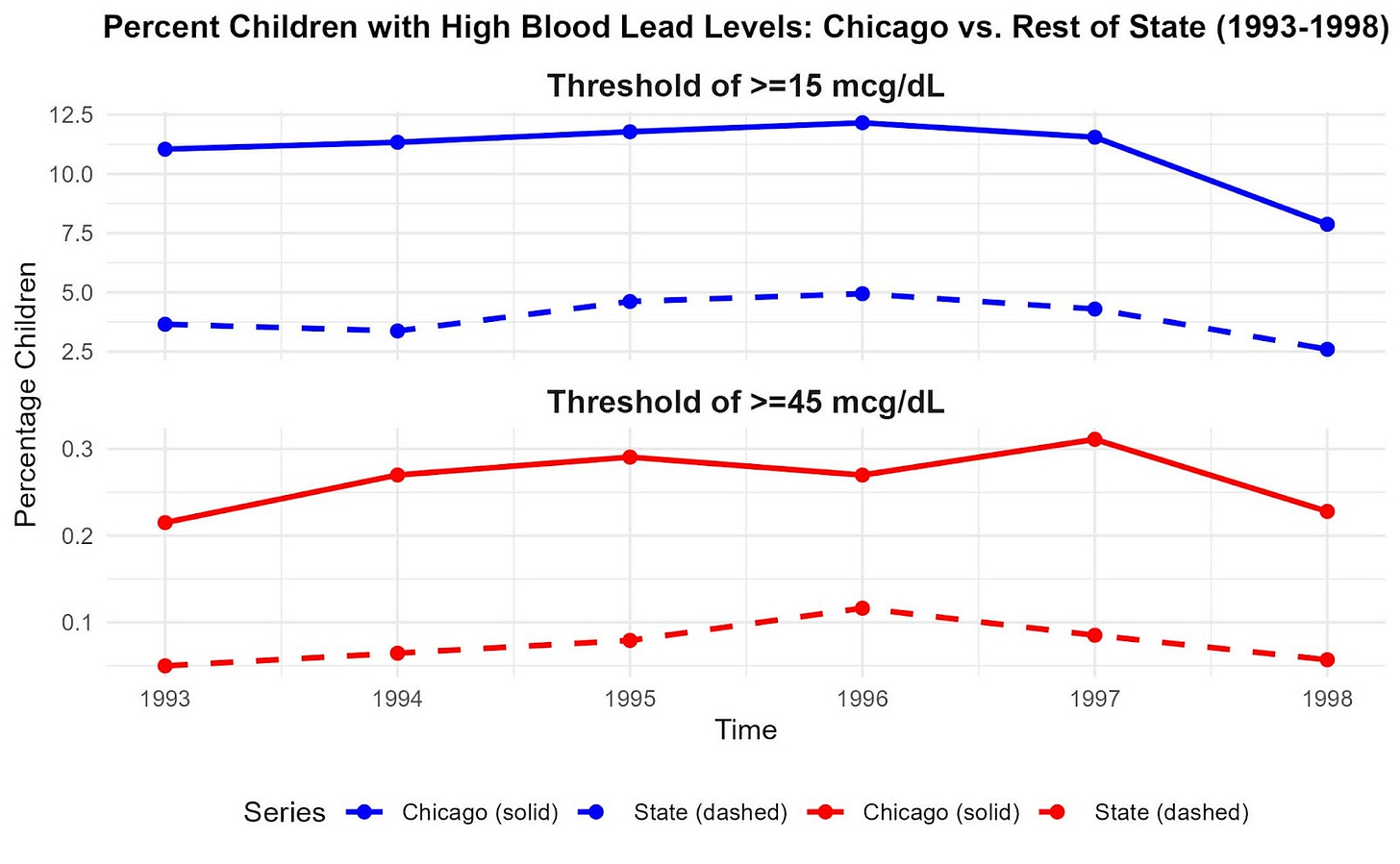

Chicago exemplified this crisis. The city had become notorious for its extensive use of lead service lines, which helps explain why, between 1993 and 1998, Chicago had to test between 33% and 59% of kids under 7 years old for lead exposure every single year. The results were sobering: in each of those years, roughly 8 to 12% of tested Chicago children had blood lead levels above 15 mcg/dL, compared to only 3% to 5% of kids in the rest of Illinois. (Figure 1). Even more troubling, Chicago children were consistently 2 to 4 times more likely to have severely elevated levels above 45 mcg/dL than their peers elsewhere in the state. (Brown, et. al).

My experience with lead exposure was part of a much larger story unfolding across America—one of both alarming importance and remarkable progress.

As scientists deepened their understanding of lead's effects, they reached a sobering conclusion: there was no "safe" level of exposure. This realization prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to keep lowering the intervention threshold—from 10 mcg/dL down to 5 mcg/dL in 2012, and further down to 3.5 mcg/dL in 2021. Looking back, that means kid Marcus would have been flagged for intervention under today's standards.

The progress over five decades has been nothing short of extraordinary. Through coordinated public health campaigns and policy changes—banning lead paint, eliminating leaded gasoline—America dramatically reduced childhood lead poisoning. National surveys show that, by 2016, only about 1% of kids under 11 years old had blood lead levels above 5mcg/dL–compared to over 99% in the late 1970s. Moreover, the mean blood lead level for these ages had dropped about 95% in the same period.

Still, the issue is far from resolved even in the US. In the mid-2010s, roughly 400,000 children under 12 in the United States had blood lead levels above 5mcg/dL. Probably more than a million children under 12 years old today have blood lead levels that fall above the new threshold.

Lead pipes still serve around 9 million homes in America, particularly in communities like mine in Chicago, where at least 400,000 (or 75% of all) pipes are made of lead, which is the most of any U.S. city. (Though this is hopefully changing with new infrastructure investments and regulations).

Yet the progress has nonetheless been significant, so much so that in 2011 the CDC named prevention of childhood lead poisoning amongst the top ten public health achievements of the 21st century.

Lead exposure is still a big deal today

Despite our steady progress at reducing lead exposure in the United States overall, the scope of lead poisoning is still staggeringly large internationally. Right now, approximately 600 - 800 million children worldwide have blood lead levels of at least 5 mcg/dL—that's roughly one in three kids on the planet. To put this in perspective, that's around the same number of children as the entire population of Europe. Lead exposure is particularly high in Southeast Asian countries like India, where around 200 - 300 million children had blood lead levels above 5 mcg/dL as of 2021.

Experts currently hypothesize that the most common ways these kids are exposed to lead include improper recycling of lead-acid batteries (which pollutes the air and soil), lead paint and pottery glazes, contaminated spices, water pipes, and other consumer goods like cosmetics, toys, and more.

The impacts of this widespread exposure on global health are significant. According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, lead poisoning was responsible for around 1.5 million deaths in 2021, primarily through cardiovascular disease that develops years after childhood exposure. When you include all the other health problems lead causes—diabetes, mental health disorders, developmental delays—the total burden amounts to roughly 34 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost in a single year. That's equivalent to erasing the healthy lifespans of entire cities.

In addition to these health impacts, lead’s negative impacts on cognitive abilities are associated with permanent reductions in income for those who are exposed at an early age. Rethink Priorities’ past estimates suggest that lead likely reduces the earnings of people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by about $300-$500 billion annually. These income losses are especially concerning because the value of additional income is probably much greater for the average resident of an LMIC than it is for the average U.S. citizen (who has a much higher income). Factoring in both the health and economic harms of lead, our researchers estimated that the total social cost of lead for people in LMICs is roughly the equivalent of U.S. residents losing $5 to $10 trillion (2021 dollars) of income annually.

But until fairly recently, philanthropists hadn’t paid very much attention to lead poisoning as compared to other similarly pressing global health priorities. For instance, according to the 2021 Global Burden of Disease study, the disease burden of malaria was around 55 million DALYs, or about 50% more than that of lead exposure. Yet whereas private donors spent over $900 million in 2021 on combating malaria, they only spent between $6 to $10 million on preventing lead exposure in the same year.

This is something we can–and are starting to–change.

We can solve the lead exposure problem

The scale of the global lead crisis can feel overwhelming, but history shows us that coordinated action can achieve remarkable results. The successful worldwide campaign to end lead-based gasoline demonstrates the great possibilities of reducing lead poisoning in children through effectively enforced laws and regulations. Developed countries like the United States first started phasing out leaded gasoline in the 1970s. At the turn of the 21st century, over 80 developing countries still allowed the sale of leaded gasoline in their countries, prompting the United Nations to advocate more forcefully for its global phase-out. Fast forward to 2021, the last country to allow it (Algeria) had halted its sale, leading the United Nations to declare that the “era of leaded petrol is over.”

Yet even as the global campaign to abolish leaded gasoline reached this point of success, there was still a lot of work to do on other fronts.

Take lead-based paint, for example. At the end of 2021, only 43% of countries worldwide had legally binding restrictions on the production, sale, and use of lead-based paint. That means more than half the world's nations still allow manufacturers to add lead to paint with little or no oversight. Furthermore, an analysis of over a hundred studies from around the world found random samples of paint in nearly five dozen countries contained significant levels of lead – including many with laws on the books meant to restrict lead additives. The gap between policy on paper and reality on store shelves was stark.

Fortunately, a new generation of organizations has emerged to tackle these remaining challenges head-on. Groups like the Lead Exposure Elimination Project (LEEP), which was founded in late 2020 through the Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Program, have also accelerated progress on the lead paint issue. LEEP’s team started small, selecting Malawi as their first country to work with. In this initial trial run, they sampled domestically consumed paint, worked with the nation’s government to establish a more effective paint testing and certification regime to enforce existing regulations, and coordinated with industry to facilitate the switch to non-toxic alternatives. After this early success, they expanded outreach to Botswana, Madagascar, Zimbabwe, all within their first year.

And eliminating lead-based paint isn’t the only way the philanthropists, researchers, nonprofits, and governments are working to reduce lead exposure. Pure Earth, for instance, works on a host of projects to mitigate lead exposure across the globe, such as helping developing countries build their healthcare systems’ capacity to monitor blood lead levels. They and others have, since 2020, been testing spice supply chains in Southeast Asia —a major source of exposure that many families don't even know about. Their work involves both educating the public about these hidden dangers and working with local authorities to crack down on contamination.

Around this time, the research and effective altruism communities increased focus on lead exposure as a potentially high-impact way to improve global health. For instance, between 2021 and 2024, our global health team at Rethink Priorities has helped coalesce the literature on the extent of lead exposure and the landscape of organizations working to address it, and model the cost-effectiveness of some interventions to address it.

Other research organizations like the Center for Global Development and Our World in Data have also done a great deal of work to resolve the many outstanding research issues surrounding lead exposure and communicate to the public the urgency of and solutions to the problem.

All this work seems to be bearing fruit. In one case, after a coordinated effort by Stanford researchers, local nonprofits, and the Bangladeshi government to publicize the dangers of lead and penalize spice adulteration, blood lead levels among those tested in the local area plummeted by 30%. And less than three years after LEEP’s initial work in Malawi, the percentage of paint samples in the country that contained “dangerously high” levels of lead had fallen from over 50% down to a third. Hoping to build upon this success, LEEP has expanded its lead paint work to 20 countries, which together represent around 45% of all infant births globally.

Importantly, major funders have begun to take notice. To bolster this momentum, Open Philanthropy, USAID, the Gates Foundation, and others helped launch the Lead Exposure Action Fund (LEAF) in 2024 to fund highly effective organizations to eliminate lead exposure globally. By 2027, they aim to directly invest over $100 million in lead mitigation efforts and help secure more than $50 million in additional annual funding commitments from other global health organizations going forward. If this succeeds, that’ll be more than quintupling of the amount of philanthropic resources that went to lead mitigation just six years before.

Coming Full Circle

Even on a daily basis, I am reminded of how close to home the issue of lead poisoning can be. From 2020 to 2023, I lived in an apartment not a five-minute walk from the University of Chicago, nestled in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the city. Despite this privileged location, I never drank the tap water once during those three years. My apartment, like so many in Chicago, was served by lead pipes. Instead, my wife and I relied on a water pitcher with a lead filter—a $70 monthly expense that became as routine as paying for electricity.

That $70 represents both my privilege and the broader injustice of this crisis. My family is but a tiny fraction of the generations of people who have been impacted by lead and continue to be. Millions of families around the world face the same contaminated water, the same lead paint, the same toxic exposure sources, but many don't even know the risks exist. And even if they did, most couldn't afford to spend $70 every month to make their water safe to drink—the most basic of human needs.

Thinking about solving an invisible public health issue that impacts one in three kids today can be simultaneously saddening, abstract, and daunting. But it’s also incredibly gratifying to have led an organization that played some role in building this movement to address one of the world’s most pressing global health problems. And, hopefully, armed with more research, organizational capacity, and resources, we will soon be able to achieve a lead-free future for our kids.